Neovim and Swift, a Match Made in Heaven

Photo by Justin Greene on Unsplash

Photo by Justin Greene on Unsplash

Photo by DDP on Unsplash

Photo by DDP on Unsplash

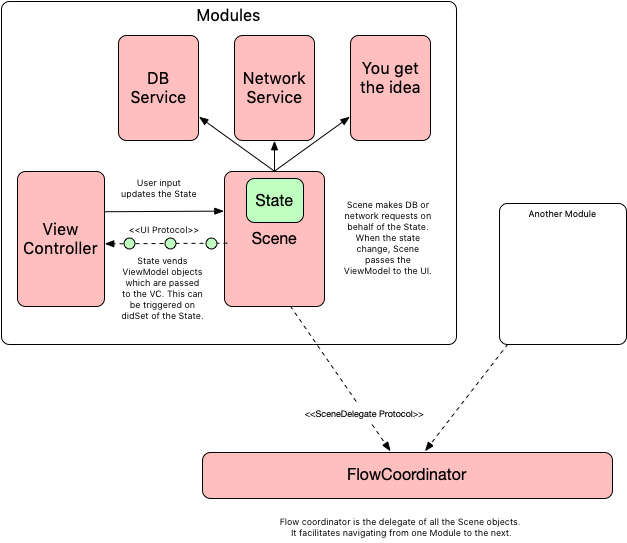

With so many iOS architectures out there these days, I was sure that one would speak to me. I’ve tried Viper, MVVM, ReSwift and others. They each had their merits but ultimately their shortcomings prevented me from using them. So what did I do?? I Invent one more architecture! And what is the worst name I could come up with for it? Glad you asked! I call it “Yet Another iOS Archtecture” or YAIA (pronounced ‘Yay-yeah!’).

An architecture should have goals, otherwise its just a collection of arbitrary rules which is no fun. Below I’ll describe some of the values that motivated YAIA.

Writing unit tests should be painless. This is the main goal of YAIA and everything else falls out of that. I’d like to write test without mocks, fakes or injecting anything. I’d like to avoid testing async code and I certainly don’t want to do any IO such as reading files or hitting a database in my tests. I’d like my test to run as quickly as possible.

The architecture should be flexible and light weight. It doesn’t require implementers to create classes X, Y and Z and protocols for each of those classes (I’m looking at you, Viper!). I also don’t want tests to implement stubs or mocks to facilitate testing.

Changes should be easy to make. This is related to points one and two. I don’t want to discourage users from making improvements because it will require changes in many places or might break something.

Simple. No unnecessary abstractions or classes. Abstractions such as protocols or base classes can make your code flexible but they also make it harder to follow. Every class or protocol has to earn its place. If it doesn’t, it’s out.

To achieve these goals, I cherry-picked features from a few different

architectures I had used in the past. From ReSwift,

an implementation of the redux pattern, I borrowed its emphasis on value types

and keeping data and logic in one place. In YAIA, the models that represent the business

and app logic are all value types (as opposed to reference types). The inputs

and outputs to this values-only system are also values. This makes results easy to

verify by simply making them Equatable. A nice side effect of a values only

system is that it’s impossible for it to contain any async code paths (a struct

or other value type can’t be captured by reference in an escaping closure).

This keeps tests simple and running fast.

While there are many things to dislike about Viper, one of its tenants is that services should be hidden behind interfaces. This is one place where an abstraction can be nice. Types from services shouldn’t creep into the business logic. What this means for iOS is that Core Data’s NSManagedObjects, wont be referenced in the values-only core. Instead, we copy data out of Core Data and into plain old Swift structs. These value type are then passed into our system. This allows us to test our system without instantiating Core Data objects. It also means that I can switch persistence technology without too much pain since the Core Data dependencies are contained; our business logic layer will be unaffected when we change the type of database we’re using.

I’ve described this architecture in

previous

posts but I’ll go over the

highlights here. For a given screen you’d like to build, a login screen

perhaps, the class that ties the different elements together is called a

Scene (naming things is hard). In this simple

example of a login screen I’ve

called it LoginScene. It behaves similarly to the ViewModel in MVVM. In

YAIA, it has a weak reference to the view controller via a protocol. This is

one of the few places that I use a protocol in YAIA. The view controller has a

strong reference to the Scene so that the Scene’s lifecycle is tied to the view

controller’s.

The Scene object contains a State object which is some sort of value type;

generally a struct or enum. I will discuss the State object further but

for now understand that the bulk of the logic resides here. The

Scene object may also have network or database services as

dependencies. The Scene’s job is to move data between the State object and

these dependencies (the UI is also a dependency).

It is the Scene’s responsibility to take input from the UI, a button press

for instance, and pass it to the State object for processing. At this point,

the State object might update its internal state and possibly return a

value type indicating the IO to be performed. The Scene would then tell the

appropriate interface to perform the request (eg network request).

The result of this request is then fed back into the State for processing.

If the State object determines a view transition is required, it will return

an enum representing that transition which is then passed to a flow

coordinator which handles the

transition.

To update the UI, the State will return a ViewModel instance which is

passed to the ui by the Scene. In YAIA, a ViewModel is a simple data

transfer object (a value type of course) that contains all the info the view

needs to update itself with.

How does YAIA achieve the goals listed above? Since the main

goal is to make software testable, I had to figure out what type of code

is easily tested. I discovered that if you separate the logic and state

from the IO, the state/logic portion becomes much more testable. The

easiest thing in the world to test is a function that takes values in and

returns a value. I wouldn’t hesitate to write a test for func add(a: Int, b:

Int)->Int. It takes values as inputs and returns a value. It doesn’t

have any internal state, doesn’t read from a database and doesn’t have any

dependencies that make the tests complicated. A test based on this method would

be easy to read and debug.

The opposite end of the spectrum is a class which handles all of its IO

internally and has its logic and IO coupled together. This class

may be dependent on other complex classes which must be recreated in a test

environment or mocked. When testing this code, the setup ends up being

many times longer than the actual test and verification portion of the test.

This means the tests are brittle and hard to read. Additionally, since they

take so much effort to configure, developers will be less inclined to write

tests in the first place. By making the State object a value which doesn’t do

any IO, we side step most of the difficulties above.

To achieve flexibility, I recommend using your best judgment regarding when to use the pieces above. If you’re building a screen with some text and a single button, put all the logic in the view controller and move on. This is just one approach to separating logic from IO but there are other ways to achieve the same goal. When it comes to architecture, one size does not fit all.

In the end, the specific names of the components and the exact responsibilities of a given class don’t matter. What matters it being able to write software that is easily verified by unit test. This is achieved by isolating logic in value types and away from the async code and IO. By doing that, you are one step closer to making tests work for you.

I'm a freelance iOS developer based in San Francisco. Feel free to contact me.

Photo by Justin Greene on Unsplash

Photo by Justin Greene on Unsplash

Photo by Anton Darius | @theSollers on Unsplash

Photo by Anton Darius | @theSollers on Unsplash

Recently, I’ve been discussing ways to architect iOS applications to make them easier to test. Yesterday, I stumbled upon this talk from WWDC ‘17. In this video, the presenter espouses a lot of the same ideas I’ve been advocating here. It’s a great video and I highly recommend it.

Recently, I’ve been discussing ways to architect iOS applications to make them easier to test. Yesterday, I stumbled upon this talk from WWDC ‘17. In this video, the presenter espouses a lot of the same ideas I’ve been advocating here. It’s a great video and I highly recommend it.

In my last article, I discuss the easiest path to testable Swift. In that article I list qualities that make tests valuable. Additionally, I show that business and application logic should be decoupled from volatile or asynchronous dependencies. Now I’d like to focus on the “State” object that houses all of this logic and illustrate some design decisions that will make it easier to test.

In my last article, I discuss the easiest path to testable Swift. In that article I list qualities that make tests valuable. Additionally, I show that business and application logic should be decoupled from volatile or asynchronous dependencies. Now I’d like to focus on the “State” object that houses all of this logic and illustrate some design decisions that will make it easier to test.

An experienced tester knows that certain features are trivial to test while others must be mangled and distorted before they yield to testing. Tests that are easy to write are ones that require little or no arrangement code, don’t require new classes to enable testing (ie. mocks or stubs) and produce easily verifiable output. The easiest thing in the world to test is a pure function:

In my last article I touched on a few ideas to make Swift testable. Here I’d like to demonstrate these ideas by implementing a hypothetical feature. The feature is written using TDD and exhibits these virtuous patterns. Before I go on, I’d like to describe the attributes which make a test good.

In my last article I touched on a few ideas to make Swift testable. Here I’d like to demonstrate these ideas by implementing a hypothetical feature. The feature is written using TDD and exhibits these virtuous patterns. Before I go on, I’d like to describe the attributes which make a test good.

Enlightenment is intimacy with all things. —Ehei Dogen (1200-1253)

Enlightenment is intimacy with all things. —Ehei Dogen (1200-1253)

I’m coming clean. I’m embarrassed to admit it, but I’ve been a professional software developer for twelve years and have hardly written any tests. I’ve embraced the unit testing cult a few times, but every time I did, I spent more time hacking my code to make it testable than writing new features. My velocity went into the toilet, my once beautiful code became riddled with concessions to make it testable, tests would break after small changes, and worst of all, they never seemed to surface any genuine defects. I would eventually give up with the excuse that “iOS code isn’t testable” or “unit tests are for people who write bad code”. Such hubris!

I’m coming clean. I’m embarrassed to admit it, but I’ve been a professional software developer for twelve years and have hardly written any tests. I’ve embraced the unit testing cult a few times, but every time I did, I spent more time hacking my code to make it testable than writing new features. My velocity went into the toilet, my once beautiful code became riddled with concessions to make it testable, tests would break after small changes, and worst of all, they never seemed to surface any genuine defects. I would eventually give up with the excuse that “iOS code isn’t testable” or “unit tests are for people who write bad code”. Such hubris!

In my last post I explained some of the common anti-patterns that developers fall into. In this article I’d like to explore some architectural principles that help make code more robust and extensible. Like all ‘rules’ in software development, these are really only guidelines, so if something feels awkward or forced, it probably is.

In my last post I explained some of the common anti-patterns that developers fall into. In this article I’d like to explore some architectural principles that help make code more robust and extensible. Like all ‘rules’ in software development, these are really only guidelines, so if something feels awkward or forced, it probably is.

Being a freelance iOS developer, I get the opportunity to work on a variety of projects, written by developers with varying degrees of experience. This has given me the opportunity to catalog the most common iOS anti patterns or ‘Code smells’ I’ve smelt. I will enumerate the most common smells and some possible solutions to guide you on your path to mobile app nirvana.

Being a freelance iOS developer, I get the opportunity to work on a variety of projects, written by developers with varying degrees of experience. This has given me the opportunity to catalog the most common iOS anti patterns or ‘Code smells’ I’ve smelt. I will enumerate the most common smells and some possible solutions to guide you on your path to mobile app nirvana.

Developers, repeat after me, “My app is not a web page”. Again! “My app is not a wep page”. It seems that most developers are writing their mobile apps like they did web pages in the 1990’s. They makes requests to the server, put the app into a waiting state, and display the response in the UI. If they are offline, an error is reported to the user and the app is unusable. This experience is fine for a webapp in the browser with little or no local storage and a ubiquitous network connection, but falls short in the mobile world.

Developers, repeat after me, “My app is not a web page”. Again! “My app is not a wep page”. It seems that most developers are writing their mobile apps like they did web pages in the 1990’s. They makes requests to the server, put the app into a waiting state, and display the response in the UI. If they are offline, an error is reported to the user and the app is unusable. This experience is fine for a webapp in the browser with little or no local storage and a ubiquitous network connection, but falls short in the mobile world.

In my previous post I taught you how to wrangle your game initialization code in order to keep it from breaking with every refactor. Today, I’d like to talk about event handling and how to get a handle on it (pun intended). If you’re anything like me, your event handling code (generally your touchesEnded:withEvent:) is the longest method in your whole application; littered with switch statements, if/else clauses and enough boolean flags to make George Boole turn over in his grave.

In my previous post I taught you how to wrangle your game initialization code in order to keep it from breaking with every refactor. Today, I’d like to talk about event handling and how to get a handle on it (pun intended). If you’re anything like me, your event handling code (generally your touchesEnded:withEvent:) is the longest method in your whole application; littered with switch statements, if/else clauses and enough boolean flags to make George Boole turn over in his grave.

Writing games is hard. Writing games for iOS is even harder. Typically, one of the most fragile and error prone parts of a game is the loading and initialization process. For obvious reasons, it is also one of the most critical pieces of your app. By using a sequencer, developers can define dependencies for steps in their loading process thereby removing some of the brittleness and instability from their game.

Writing games is hard. Writing games for iOS is even harder. Typically, one of the most fragile and error prone parts of a game is the loading and initialization process. For obvious reasons, it is also one of the most critical pieces of your app. By using a sequencer, developers can define dependencies for steps in their loading process thereby removing some of the brittleness and instability from their game.