Pt. 2 Testable Swift

In my last article I touched on a few ideas to make Swift testable. Here I’d like to demonstrate these ideas by implementing a hypothetical feature. The feature is written using TDD and exhibits these virtuous patterns. Before I go on, I’d like to describe the attributes which make a test good.

In my last article I touched on a few ideas to make Swift testable. Here I’d like to demonstrate these ideas by implementing a hypothetical feature. The feature is written using TDD and exhibits these virtuous patterns. Before I go on, I’d like to describe the attributes which make a test good.

What to Strive For

- Tests should be easy to read. All setup code is located in close proximity to the test condition. It is clear what the setup code does and why it is required. The test is concise and only includes code relevant to the test. Readers can easily grok which product requirement the test demonstrates. Testing enables others to understand the code as much as it enables the writer to create it.

- Tests should be easy to write. Only a few lines of code are required to arrange the test. The test executes synchronously and no mocks or stubs are required to implement them. If there is friction in writing tests, developers will skimp on them.

- Tests should not make production code more complex. Adding abstractions or making private APIs public to facilitate testing muddies the intention of the code. Tests enable developers to write simpler production code.

- Tests should not be brittle. As long as the API under test doesn’t change, wild changes to the implementation can be made and test failures will only be seen when a feature is broken. The confidence to make dramatic changes is the true power of unit testing.

- Tests should execute quickly. While practicing TDD, the tests are run dozens of times a day. If you must wait for the simulator to spin up each time, momentum will be lost.

Sounds nice doesn’t it? Most people who dip their toes into the TDD end of the pool have the opposite experience. Testers create several mocked classes and write tens of lines of setup code for each test. The suite runs painfully slowly making TDD impossible. Changes to the system break or invalidate dozens of tests, making refactoring harder instead of easier.

An Example

My approach to this article is to assign myself a hypothetical feature and implement it using TDD. I followed a few heuristics which make it much simpler to write testable code.

So what is this secret testing sauce I keep alluding to? The idea is to keep the logic and state isolated from the IO or any other volatile dependencies. By ‘logic and state’ I mean business rules and domain models, I also mean the state required by a view controller, or the queuing and prioritization logic required by a network controller. In this instance ‘IO’ means disk and network access, UI interactions, anything to do with GCD as well as DispatchQueues and even timers. As long as all IO have been removed from the code under test, writing the tests will be simple.

The feature I’ve decided to build is a BLE pairing screen. The user is shown all broadcasting BLE devices in their vicinity. They are able to tap a broadcasting device and give it a nickname which adds it to the local Core Data store. In this scenario I have three IO devices; the CBCentralManager, the CoreData repo and the view controller displaying the list of BLE devices. I also added cell animations when a users adds, deletes or renames a device. The complex logic behind this feature is where TDD really shines.

I want to stress that this is not another “MV* architecture will fix your problems” article. The example here is just one implementation illustrating these principles. There are many ways to isolate logic from volatile dependencies. These guidelines apply to all software project, not just view based ones.

Bringing It All Together

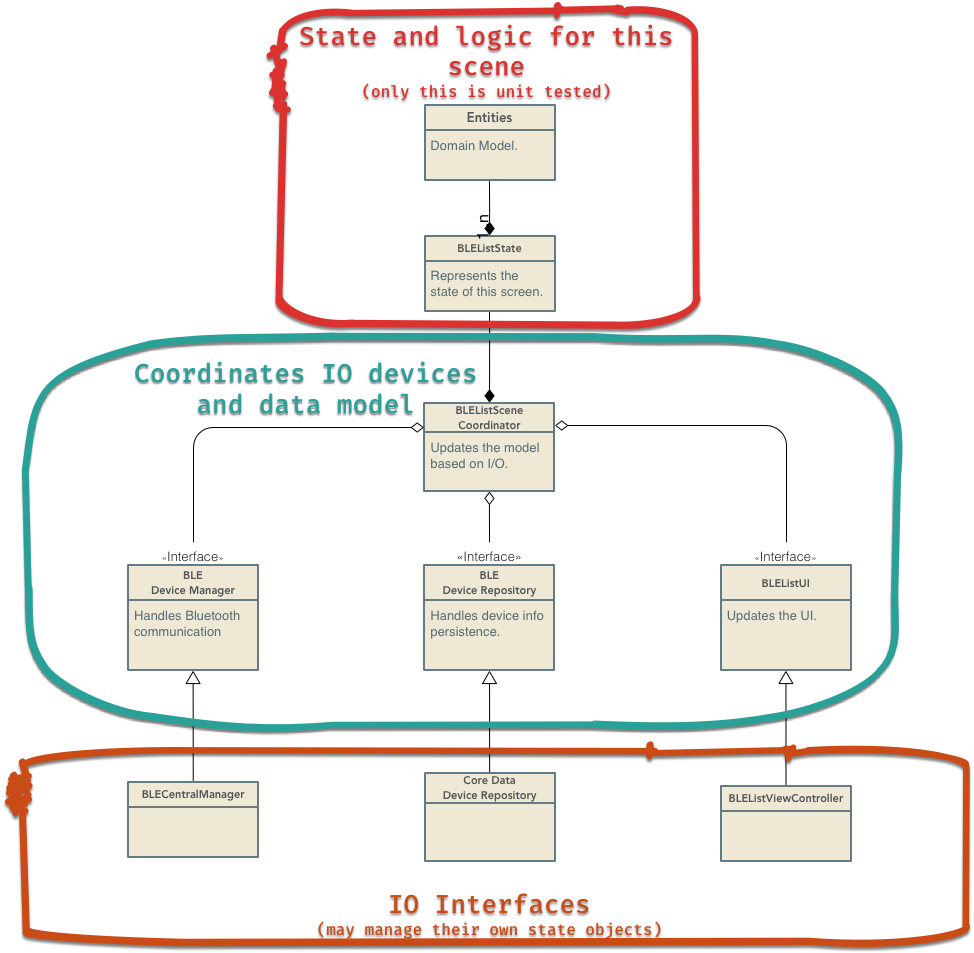

In the diagram below, I’ve indicated how the IO devices integrate with the UI logic:

As you can see, the red box is the system under test (SUT). It contains all of the classes that we are testing for this screen. At first glance, it might appear that we’ve failed to test a great deal of the system. On closer inspection, we can see that all the interesting logic and data structures are contained solely in the red box. The green box is only responsible for shuttling data back and forth between the IO devices and the state object. It has a cyclomatic complexity of one. The three IO devices in the orange box may contain their own logic and state (queues and retry logic etc) but would be covered under a different set of tests.

An Aside on ViewControllers

The view controller on the bottom right is especially interesting. We are so used to the view controller being the real meat and potatoes of any screen, its hard to imagine it not containing anything worth testing. In this example when something in the model changes, a new TableViewModel is pushed to the view controller along with a RowAnimations object (both structs) describing the animations. All the view controller does is copy values out of that model and into the table view cells and run the animations. Again, there is no logic in the VC, it has no knowledge of the underlying data it represents, it simply updates itself with the model which is pushed to it. The result is that the VC is easy to reuse.

There is no logic in the TableViewModel, it is simply a data transfer object. The values in these data transfer objects are what we will be verifying in our tests.

In Conclusion

Using this approach won’t uncover every conceivable bug in your project. There will be issues integrating the repository, the BLE interface and the UI. We will cover the interaction of those components using integration tests. If each component is rigorously unit tested, we will be more confident when we go to integrate them.

In my next post I’ll illustrate some patterns and heuristics I use to keep Swift testable. See you next time!

I'm a freelance iOS developer based in San Francisco. Feel free to contact me.